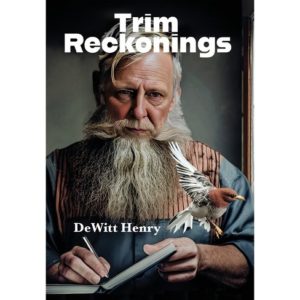

Trim Reckonings is a masterful collection of poems by DeWitt Henry, poet, essayist, memoirist, prize-winning novelist, and founder of the prestigious literary magazine Ploughshares. We find the author’s passionate love of language in this work, and, as in his other poetry collections, a sheer multiplicity of words, usages, and expressions. This collection is highly conceptual, often answering the question “What is the nature of?” What is the nature of charm, rocks, fun, games, of risk, of nudity, of narrative and perspective? From poem to poem, Henry digs deeply into his subject.

One interesting issue Henry considers is the status of material things. What confers meaning on a given object? What gives it identity? It’s a philosophical question. In “Medallion,” family heirlooms become associated with the poet’s sense of family identity, the most fascinating to the poet a gold medallion. A particular object’s meaning depends on one’s perspective. To the poet, it was an emblem of his mother with her photograph “posed and colorized,/and mounted under glass.” It was her youth and beauty, but to the poet’s mother, the medallion was “an artifact of vanity.” To the poet’s sister, it’s an heirloom to be passed on to her “daughters and grandsons.”

Similarly, in “Gas Mask,” identity depends on context. The gas mask from the Battle of the Bulge, bequeathed to his family by the poet’s uncle, is now a mere plaything. Originally a mask for a gas attack in war, now it’s a Halloween object. Later, when the mask was gone—lost or stolen—it lost all connection with context—and thus meaning. Another WWII war trophy, a “canister with a swastika on the lid,” containing the mask, is also a gift to the narrator and his brothers. No object has meaning on its own. A 9 mm Luger is no longer, exclusively, a trophy from the war. Meaning, or in this case, the ontological status of an object, depends on use—on its relation to the possessor.

In “On Heart,” Henry takes up the issue of human nature and biology. He considers numerous usages, numerous meanings, of “heart,” and then poses a question: “Meaning too much, can ‘heart’ mean anything at all?” Yet he digs even deeper into its nature, yielding more and more expressions and meanings. We can’t limit the word in its numerous applications; it’s more likely that usages will only expand, given that we are emotional creatures who relate to what’s “heart felt”—and what’s not, or what’s a “False heart. Heartless.”

Another poem dealing with human nature is “Generous.” We think of “generous” as “Opposed to stingy,” but at a more basic level, it comes from “Gen,” which comes from the Greek for “race, birth, or kind”—that is, “humankind, species, kin.” The word generosity is herein linked to “genitals,” which takes us to “generation” and “Ancestors” and “gene pool.” In this poem, Henry goes to the very root of a human’s most fundamental biological nature—as well as moral nature. King Lear, he reveals at some length, “explores evil and its genesis” (italics mine).

Biologically, humans are quite limited but wish to escape their limitations. Birds fly, but humans seek to break their human barriers, as Henry shows us in “The Birdly.”

Human flying takes some technological doing: “Lower yourself to knee pads,/lie spread-eagle with arms and hands/on flappable paddles./Fit on VR goggles, raise face to fan,/get strapped in; and you’re flying!” Through applied science, humans can create a “‘full-body flight simulator’” and “flappable paddles.” Like birds, they can “Dive, swoop. Feel wind.” Yet there is unquestionable risk: “Flight ends by crash/or power switch.”

As in his other poetry collections, Henry often engages in clever word play. In “On Bars,” the poet covers such expressions as “behind bars,” “bar none,” “raise the bar,” “clear the bar,” “cross the bar,” and “bar the gate”—or common usages such as “bars of gold” and “bars of music.” But notice, too, the root word “bar” in “barricades,” “barbarian,” “barrels,” and “bargains”—and, also humorously, in famous people’s names, like Attorney General Barr and Barack Obama. It’s the sheer love of, and appreciation for, the multiplicity of usages and meanings that drives this poem.

Trim Reckonings is a masterwork of meaning and craft. Through Henry’s perceptive treatment of his subjects in the forty poems that make up this collection, we become reacquainted with what we may have thought we already knew—but didn’t. For Henry gives new meaning and expression to his numerous subjects. Through his fresh eye, the common becomes uncommon.

Jack Smith is the founding editor of GHLL. He currently has six novels in print, with two more coming out in the fall, as well as four nonfiction books. His novel Hog to Hog won the 2007 George Garrett Fiction Prize and was published by the Texas Review Press in 2008. His stories, reviews, interviews, and articles have been published widely.