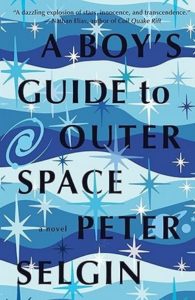

A Boy’s Guide to Outer Space by Peter Selgin (Regal House Publishing, November 2024; 308 pp; $19.95; ISBN 9781646035113).

Peter Selgin is the winner of the Flannery O’Connor Award for Fiction. He is the author of the recent novel Duplicity, memoirs, children’s books, and plays.

Selgin’s new novel, A Boy’s Guide to Outer Space, might be mistaken for a young adult novel, but it’s a novel on the order of Huckleberry Finn, an adult novel about boyhood. Increment by increment, it builds and builds, drawing the reader into the slough of despond that is this boy’s world—and the adult’s inherited guilt.

The novel, set in 1963, opens with a star exploding. How fitting, for the protagonist, Leopold Napoli IV, dubbed “Half,” feels a great need to “touch something of the infinite.” He loves astronomy. Half studies the planets, the stars. He likes John Glenn. Is such a dream possible in small-town Hattertown, Connecticut? Is such a place the right place for cosmic dreams?

Perhaps so. For one day his peer group, the Back Shop Boys, whose fathers work in the town’s one remaining hat factory, discover a huge Mysterious Object, as big as a furnace. Half manages to break a piece off and deliver it to a rather off-center man named Virgil, a man who spotted a flying saucer back in 1954 and who has a lot of alien memorabilia in his place, sent to him from other alien enthusiasts. Perhaps this Virgil will be able to identify this unusual find. Is it a boiler? Is it radioactive? Whatever its makeup, Half must watch out for aliens, Virgil informs him. But then maybe one of the Back Shop Boys is right: Virgil is an “‘expert nut-job!’”

The boy’s world of this novel also includes a mysterious man, the Man in Blue. “All we knew then was that he walked around town in blue coveralls gathering things in a rucksack he wore on his back.” According to one member of the group, “‘We’ve got to get the goods on him.’” To the boys’ fertile imagination, the possibilities of this stranger’s identity seem endless: ”A deaf dumb diseased Commie queer spy lunatic escaped mass murderer. The Man in Blue was all those things and anything else we wanted him to be.” For Half, the discovery of the Man in Blue’s identity and history becomes an unveiling, bit by bit. Here is a stranger, when fully unveiled, more sinned against than sinning.

As is Half’s stepfather, who can never measure up to Half’s dead father, but who tries, bestowing many a gift on Half, who sees this as a way of buying his love. Despite the man’s off-putting, cliched language and his monomaniac fixation on the value of hats, when he has a stroke, Half comes to see how wrong he was to treat his stepfather dismissively.

This is a novel with compelling characters. Half himself is an encyclopedic storehouse of trivia. For instance, “The average mosquito drinks five-millionith of a liter of blood per serving.” And: “the sun is 330,330 times larger than Earth; Venus is the only planet in the solar system that rotates clockwise; in Nakhla, Egypt, on June 28, 1911, a dog was killed by a meteor.”

Half’s mother is a woman who feels like she’s wasted her life. She greatly regrets marrying his father, has remarried, and spends most of her time drinking. As a sixteen-year-old, she’d hoped for much better, joining the Radio City Rockettes. She’d be a chorus-line dancer. But any hope she had of that career dried up when a man groped her and she ended up going back home.

Half’s stepfather is a colorful character, with a different pipe for each day of the week. He has a quirky list of things he cannot tolerate, including “unpolished shoes, untrimmed fingernails, belching, Bolsheviks, beanies, and beatniks.” He’s constantly saying “Upon my word.” When President Kennedy appeared in public without a hat, Half’s stepfather, a total hat enthusiast, wrote him a letter. Men who go “hatless,” he deems as “brutes, beasts, barbarians.”

This is a novel filled with real life. It’s deadly serious, but it’s also humorous. Overall, there’s an unnerving sense of doom, but felt life, as we know, is so often joy mixed with woe, laugher as memorable as tragedy. Selgin’s novel is a tour de force of lives lived and spent.

Jack Smith, founding editor of GHLL, is the author of 7 novels and 4 works of nonfiction. His eighth novel, Madness, the first in his series FATE, will be published soon by Pierian Springs Press. His ninth novel, Mayhem, the second in his series, will be published later in 2025. Presently he’s at work on the third in his series, Chaos. He has published numerous book reviews, articles, and interviews. Until it folded, he was a regular contributor to The Writer Magazine.