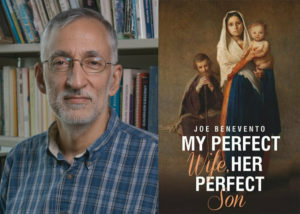

My Perfect Wife, Her Perfect Son, by Joe Benevento. Addison & Highsmith, 2023

Barnes & Noble

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/my-perfect-wife-her-perfect-son-joe-benevento/1142006303

Next to nothing is known about St. Joseph; he appears in only two of the gospels, which show some minor disagreements with each other and take different approaches to reconciling facts (known to living witnesses in that first century) with the expectation that those facts will line up with old prophecies about the Messiah. We see dueling accounts of descent from King David. Joseph plays a supporting role in the Nativity story (an angel visits him with advice and instructions), the Flight to Egypt (another angel, more directions), the less-iconic return from Egypt (again an advising angel) and the Passover visit to the Temple when twelve-year-old Jesus reveals that He’s something more than the simple son of a tekton (a skilled craftsman in the building trades).

That’s it.

In that first episode, Joseph is betrothed to Mary, who turns up pregnant “before they had come together,” and, yes, that would of course be a deal-breaker for an awful lot of men even in the present day. In a moment of exceptionally terse psychological characterization, we’re told that Joseph was “dikaios” (“upright,” “righteous,” but without the associations those words have for us — unbending, rule-bound) and didn’t want her made an example (literally a “paradigm”), so he intended to ….mmmm…. “apolousai” …. “dismiss her” would be right, but “set her loose” is most literal. And then comes the angel.

That’s not many dots, but they have compelled countless writers to connect them in myriad ways over twenty centuries.

As it happens, I’ve had substantial experience of the two chief streams of that vast imaginative literature. In my southern, rural Sunday School, we’d often hear about the Holy Family (never called that; it would have sounded way too Catholic). Jesus was an obedient son, and frankly, a real pain: all of these stories carried the implicit point that He never lied, or stole things from the pantry, smacked His pseudo-siblings around, never fussed, cheerfully ate His vegetables, and took actual pleasure in doing His chores — unlike you little heathens. Now, let’s remember, we were little kids, not actually literate yet, and we had no idea what was in the Bible and what was not, no way to know that they’re just making this stuff up. Folklorists call it “parascripture;” if it lasts long enough, gets enough credit from the right people, it might be classed among the “apocrypha” or even “deuterocanonical books.” But it was just gospel fanfic, with an agenda: this is what good people look like, and it doesn’t much resemble your wretched family.

I eventually became a medievalist, and became aware of a vast folklore, “Tales of the Boy Jesus,” in which He was actually something of a scamp, and not always in a charming way — occasionally prone to abusing His superpowers (calling down fire from Heaven on a playmate who bodychecked Him during a soccer match; He undid it of course). Joseph often took on a comic role, something like the Captain in the Katzenjammer Kids. The tales were often edgy, even downright bawdy. The Middle Ages were comfortable with a lot of things Missouri in the early sixties wasn’t. The stories regularly flirted with scandal.

So we had on the one hand the usually-tedious Saint’s Life (aka “legenda,” that is, “something to be read” also called a “vita”), a pious fiction filled with miracles — and the reader’s only permissible attitude is reverence, or, on the other, a ribald retelling in the mode of Married With Children. These are the two obvious and established traditions of filling in the gaps that My Perfect Wife, Her Perfect Son acknowledges and studiously, significantly, declines to follow.

Instead, Benevento has sought to imagine a very ordinary human being in direct confrontation with the extraordinary. His version of Joseph is neither a genius nor a dolt (the way many medieval tales play him, strictly for laughs). Similarly, he is a person of orthodox belief and conventionally good behavior — not On Fire With The Spirit, but also not defiantly irreverent or, like the pre-conversion Augustine, torn by the passions of a great soul. He is not particularly burdened with imagination, and that is what makes the process of his coming to terms with the Unimaginable a solid story, and one Benevento tells well.

It’s a first-person that might as well begin “So there I was, minding my own business …” Literally. In the first scene, he’s taking a break from his dusty shop, stepping out into the dusty dooryard, when his betrothed appears to ask him if he’s had a visit from the Angel Gabriel, as she has — and she gives an account of the Annunciation.

This is exactly the moment that so many re-tellers have rendered either as majestic quasi-liturgy or as farce, and it’s crucial that Benevento steers a different course altogether. The carpenter is equal parts bewildered and annoyed. As you or I would be. There is no “Then Joseph flew in anger/ in anger flew he…” He assumes she’s bonkers, he wonders if it’s some scheme on the part of his in-laws (Joachim and Anne are prosperous folk who thought Mary could do a lot better — this is a world of very familiar social and psychological types). He tries to return to work, botches it — as we would do — and calls it a day, to go home and fret about it. As you or I probably would.

Cue the Messenger.

Joseph’s nocturnal visitor does indulge the impulse to comic relief, if mildly; the Angel Schlomo is drawn with some Borscht Belt touches, and a tendency to sarcasm. There’s a bit of writerly legerdemain in this, which only comes clear if one imagines the character gone (or worse, reduced to a hand-patting Victorian seraph whispering there-there-dear). Joseph’s relative equanimity in the face of cosmic provocation makes a reader restive: we mutter “you can get mad, buddy. You got a right!” That negative energy has to be grounded someplace, and this angel serves the purpose. What’s further interesting is that Schlomo, a minor character, nonetheless exhibits some development into greater dignity, in a process that — for his few and brief appearances onstage — seems to track Joseph’s equally undramatic growth into acceptance of his role in things much larger than himself. The novel shows no particular interest in the more abstract aspects of revelation theology, but it does represent Joseph’s faith as a recognizable road of maturation.

And that is perhaps the core of the novel: Joseph is a saint who does not present himself to us or seem to himself to be particularly saintly. He is entirely human. Even as you and I.

Now, it would be disingenuous to write this review as if I had not known and worked with the author for thirty years. I do not think I will give offense or surprise anybody who also knows Joe by observing that he is personally pretty free of pretentiousness, though an accomplished scholar (and at many points the text tips its hand to reveal diligent study of history, archaeology, Jewish custom and ritual, even climate and geography). While the story is told without so much as a nod to the Patrilogia Latina, it is a deeply faithful and orthodox realization and imaging of incarnation theology: the Word became flesh — quite ordinary flesh. Dwelt among people like us. Who were mere flesh and yet incorporated, structured into something much larger. Joseph becomes a saint. Yet this extraordinary man remains his quite ordinary self. All saint, and all human. “History is God writing straight on crooked lines.” “The stone which the builders rejected..”

Given the sub-text, spoilers are not an issue (or so one hopes; when the film Titanic came out, someone on queue was reported as saying to a companion “I heard that two minutes of the sinking cost ten million dollars to film,” and somebody else in the line said “well thanks a lot for ruining it, mister!”) What of the other notable characters? The title, obviously Joseph’s words, foregrounds it as an account of “My Perfect Wife, Her Perfect Son.” Given what anybody coming to the story already knows, it sounds at least potentially irritable. And Joseph is ordinary enough that he is capable of irritation, exasperation. I mean it is a bit much, right? Benevento, at turn after turn, seems aware of diverging paths to low comedy and high drama, but takes a different road. The storytelling is emphatic about the daily: people work with their hands, they walk through landscapes, they bake bread, they tend camels (the camels spit). They are, again, ordinary people in a workaday world of social and domestic detail.

Mary is not so much a character for readers to react to as a phenomenon for Joseph to interact with and to reveal and ultimately develop himself. She is not an abstraction, but she is a glyph. The text indulges no speculation, no theological voyeurism (again, take it from a medievalist: that is a well-worn narrative path). And no mariolatry. She is something of a mystery to her husband, but then, isn’t each of us a bit of a puzzle to all the rest of us?

Remember what I said about the Boy Jesus narratives I heard at First Baptist Church of Oakville? The young Jesus of MPWHPS is a pretty ordinary sort as well; Benevento does not game out — as scholars have done for centuries — how His dual natures, divine and human, would deal with one another in the turbulence of adolescence. That’s not the point. Rather, it’s about growing in capacity to live with forces much larger than oneself, without grasping for understanding. As the novel progresses through the synoptic narrative, the tone deepens, darkens, the comedy recedes, as the seriousness of what they are all involved in becomes more patent — even if exactly what’s to come is unclear. Joseph accepts the fact that he’s on a need-to-know basis, and some things are above his paygrade. Like Huckleberry Finn or Don Quixote, this novel begins playfully and grows in seriousness as the gravity of its matter becomes more apparent.

But it never becomes sermon or hagiography. It is not in fact a religious novel so much as it is a study in character development, psychology. From beginning to end, it is the story of a man who is perfectly human (that is, quite imperfect) who must make his peace with his perfect wife and her perfect son. In some ways, it serves as a meditation on the famous phrase in Ephesians: “We are not just called to be saved; we are called to perfection – developing the mature, spiritual character we must have to serve in divine matters.”

Adam Brooke Davis, managing editor of GHLL, has published fiction, poetry, essays and scholarship. He teaches folklore, mythology, medieval studies, linguistics and creative writing at Truman State University.