Joe Benevento:

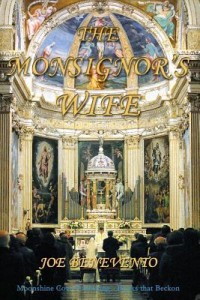

The Monsignor’s Wife

Joe Benevento: The Monsignor’s Wife. Moonshine Cove, 2013. 266 pps ($12.74 ppbk; Kindle edition $6.75)

Joe Benevento: The Monsignor’s Wife. Moonshine Cove, 2013. 266 pps ($12.74 ppbk; Kindle edition $6.75)

It’s a little unsettling to realize that a guy you’ve known for two decades, a close colleague and collaborator who often sits in the pew behind you on a Sunday, spends a lot of time thinking about how to kill people.

In detail.

Oh, and it’s about a randy priest with a steamy secret life, and how people associated with that secret existence start turning up dead.

GHLL’s own Joe Benevento, with near a dozen volumes of fiction and poetry behind him, takes on the mystery genre in The Monsignor’s Wife. Not an untrodden path for an academic, though he does not choose the campus novel. Rather, he returns to the Queens of his upbringing, with its raucously non-whitebread demographic, and its intricate web of loyalties – family, friends, affiliations of school, church and neighborhood (that last thing counts for more and for longer in this world than it does for most of us. Do real neighborhoods even exist anymore?). Or the really complex class-dynamics, the tensions of profession and occupation – which are by no means the same thing, and do not relate in a simple hierarchy of prestige, as we observe from the byplay between the protagonist – a priest – and his hardboiled gumshoe brother. Or the whole family, really, who are deeply ambivalent about Tony Cupelli’s education, his growing celebrity as a writer and as left-of-center theological controversialist.

These things are for me the center of the novel, and they will draw in those who have inadvertently educated themselves right out of their family and social class of origin – the theme of Richard Rodriguez’ sole (but superbly) compelling piece of writing, Hunger of Memory. It’s a world of intelligent people, meaning that of course ideas matter to them, but people of feeling as well, for whom ideas are not the only things that matter, or the things of supreme importance.

Sex, for instance. That matters, as most of us get around to acknowledging. It does not cease to matter because one enters the priesthood, even if the vocation is genuine (a question that lurks for this ambitious and successful careerist, soon-to-be-monsignor). “Of all perversions, celibacy is the strangest,” said various people, according to various sources on the internet. And I admit I was prepared for a working-over of soft and familiar polemic targets. But the Church and its practices are neither villainized nor valorized here. Neither is Cupelli’s toxicity due to Freudian repression (at least not of his libido) nor to post-sexual-abuse-scandal hypocrisy. Any of that would be cheap and easy. His problems are those of a character with many resources, and with flaws equally numerous and deep. His keenest and most ferocious critic, who also knows and loves him well, gets it – he’s intellectually brilliant and morally, emotionally obtuse at best: “Is there no level at which your hypocrisy doesn’t at least begin to bother you?” she asks in what I regard as the novel’s understated, pivotal moment – a sort of reverse-confession in which Tony has a final chance to be honest with himself. Muffs it.

For those who are engaged even at the level of philosophical sparring by feminist and marian theological traditions in the Catholic church, there’s a running debate that’s simultaneously accessible and intellectually meaty. More importantly, that discourse provides opportunities for characters to characterize themselves, as sterile intellectuals, or as more genuinely engaged with human aspirations and problems, or yet again as frankly anti-intellectual. For his own part, it is not clear that Tony was ever really interested in anything except being a bishop, and we can see that he’s tragically opaque about even that – for all his subtly and articulateness, it’s doubtful he could tell you why he wants that.

I have not made Tony Cupelli sound very appealing. He is a genuinely interesting protagonist, because he is so thoroughly, credibly hard to like. He is authentically learnèd, with a wide-ranging and sincerely inquisitive intelligence. He has moments of human insight, but as we know from reading any given writer’s biography, that’s no guarantee of self-knowledge. His is a speculative mind, and the ideas he puts in play are often interesting, but we never know whether he raises thorny questions (regarding, say, women’s ordination) because they genuinely trouble him, or because he likes the sound off his own voice when he talks that way, or because he recognizes that other people do. He is probably unaware of his own narcissism, and yet that’s hardly more than annoying, because it’s the vanity of a child. That’s a believable psychohistory for this character – he has no experience with adult relationships, and he’s used to being fawned-over. Children can be charming, of course, and any number of women, particularly, seem to find this one engaging.

Which, with Homeric inevitability, is the beginning of evil for him.

Mystery matters as much as sex, in a mystery novel. The Monsignor’s Wife has suspense, indirection, detection. It’s a classic whodunit. Myself, I guessed wrong, though I acknowledge I certainly had everything I needed to solve the case. There is craft here, though it’s unobtrusive. Fans of Poe’s Inspector Dupin, or of Borges’ short fiction, will find Easter eggs hidden here and there. There’s a narrative that carries its own weight, but also a gravity of thought and a grownup inquiry into character that make it a full novel.

The book was originally conceived of as a one-off, if not merely an experiment, but the results are solid enough that further doings of Tony Cupelli and his friends are in the offing. And worth looking forward to.

Adam Brooke Davis teaches folklore, medieval studies, writing and linguistics at Truman State University. He has published fiction, poetry, essays and scholarship, and serves as managing editor of GHLL.