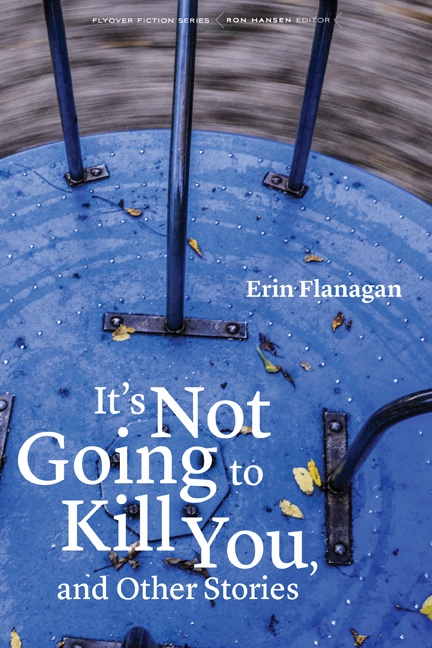

Erin Flanagan’s It’s Not Going to Kill You

Bison Books (Flyover Fiction Series) 208 pps; Sept 1, 2011

Bison Books (Flyover Fiction Series) 208 pps; Sept 1, 2011

- ISBN-10: 0803246293

- ISBN-13: 978-0803246294

The opening sentence of the opening (titular) story is a sort of dare: “Candace wonders which is a bigger sin: to take communion and not mean it or skip it all together, and if she doesn’t believe in God, does it matter one way or another?”

Easy to imagine readers who take that fragment of internal monologue as the anguished bewilderment of someone who at least remembers what it was like to have faith, or others who read it as the silent sarcasm of someone so-totally-past-all-that. And those who take it as the one would fling the book aside in disgust upon discovering it’s the other.

Well, as it turns out, it’s neither, but the initial puzzle sets us up as participants in a reflection on whether there is such a thing as the Self, what such a thing would be, and how one would know. Not lightweight questions, and the people whose lives test them out are no triflers. The twelve stories in It’s Not Going to Kill You represent a deep, sustained and serious intellectual inquiry, yet the prose is direct, transparent, rarely calling attention to the thinking as such. It’s philosophy for people who have real lives, and have to go to work in the morning.

In this collection, consistently, people think of themselves in roles, and see themselves performing life in such a way as to cause others to believe them into being what they claim to be. A man blithely announces to his recently-divorced wife that “he wanted to be an ex-husband who would be there for her.” The protagonist instantly recognizes this answer as nauseatingly self-serving, and of course readers do likewise, but Flanagan wants us to catch Candace, and ourselves, in the act of inference itself. Candace is aware that she’s doing it, and so are we. The program grows clearer as she returns to her childhood home after a long absence and cuddles her young son in the bedroom that was once hers. In describing to him the “long-gone décor” she tries to conjure the equally gone girl that she had been. She is partially, only partially successful, even for herself. Personal history is not illusory, but it is fugitive. We feel that, and this is what makes such profound philosophical investigation deeply human.

When intimacy happens, these characters find themselves saying things like “I’m sorry to hear you had crabs.” And hearing themselves saying it. These attempts to contact other humans, to be reassured that one exists, are overtly concerned with epistemology and ontology and flamboyantly absurd when they are the subject of banter between two clowns killing time in the Void, a bare stage with a tree and a bench. But in a bar when you meet a man who bullied you in childhood, who has willed himself to learn suffering and to grow from it, and who has actually become a pretty decent sort of mensch, contact seems like it might be possible. And when it turns out not to be – sad. And yet affirming.

It’s the sad nature of sacrament, to be so near the Real Presence, but never…quite…there. The first visible action in the first story is a woman, possessing still perhaps a residuum of faith, leaning forward, opening her lips to take communion from a child server, and it closes with her leaning forward to kiss her son. There’s a symmetry here that never feels calculated, and that is the defining strength of the entire collection.

That might be the template, or perhaps a better candidate is the opening of the second story, “The Good Neighbor”:

I was mowing on a Sunday late in the day when my neighbor Mary stumbled from her front door and crossed her yard into mine. She began speaking over the loud grind of the mower, her hands moving harshly through the air.

We’re all trying to make ourselves heard, to get through to other people, over the noise of daily life. The speaker here, an algebra teacher, is going to have to take Mary to the hospital where her grandson, one of his students and beyond all doubt a bit of a jerk, has been taken after a car accident. There is no indication that it was his fault, but someone is dead, and there follows the saddened acknowledgement that this seventeen-year-old has become a new being. Irrevocably, he is someone who has killed a person. Throughout the collection, people take on, or at least find themselves in roles that – again invoking Beckett, who pursued many of the same concerns in a very different mood and idiom – might’ve given literal labels: the Bully, the Neighbor, the Spouse, the Child. Our Math Teacher spins back to a self of decades before, recalls learning that his college girlfriend was pregnant, and how they had presented themselves to each other, in that moment, as what they felt the crisis called for: “Her face was a mix of hopeful exuberance and dread. My reaction had been the same. We were both playing a role, trying to figure out what we were doing being adults.” Another character thinks of a recent and trifling event primarily as “an anecdote she can pull out like a shiny present to show everyone that she is a Mother who understands her Daughter.” But this same character wonders whether she’s properly in character: “Isn’t having a baby supposed to make one selfless?” She realizes she is “a greedy mother who wants first shift.” These are not clichés from a 70s version of California, shallow people narcissistically concerned with self-actualization. They want above all things to be themselves, and have the misfortune to be too self-aware for comfort, like Method Actors who have been taking lessons too long. People report their own self-understandings in terms a psychologist would instantly diagnose as depersonalization: “It’s like I’m watching it on TV.” Emptiness and fullness, emotional or physical, feel the same to them.

The interior and exterior lives are often contrasted, but with no fallback reassurance that one is more real, more genuine than the other. In “Dog People” the young mother Margie tells a complete stranger she’s met in the park that her husband is out of the picture. It’s simply not true, and she has no idea why she has presented herself in this way. We wonder – I believe we are meant to wonder — if the author is inviting us to let the tropes of erotica and certain kinds of chick-lit script us into anticipating an intrigue aimed at capturing a lover, but there’s no indication that’s any part of the protagonist’s program, conscious or otherwise. She doesn’t know why she said that, and the possibility that there might be no reason at all is so frightening that a corrupt one seems preferable. We do not know why she spends her days vividly imagining herself failing her child in the most gruesome and catastrophic ways, truly torturing herself, and then upon being asked by her weary and oblivious husband how her day has gone, replying “fine.” It seems true enough. Every story is really one of perceptions – people perceiving others, perceiving themselves, perceiving themselves through the eyes of others.

These desperate sallies at asserting a self and presenting that self to the world are not the indulgences of late-night college bull-sessions. It doesn’t get a lot more real than this: a seventeen-year old boy-man passing through a prairie town’s harvest fair with his family sees the chance for an emotional connection with another guy, and knows very well what will happen to him if he has misunderstood the cues. A little white girl admires the way her black friend’s mother dresses up each day, and the answer feels like icewater in the veins: “Your mother’s white. She can afford to be a slob.” As it does when an ostensibly helpful trucker stops by a stranded couple, and looks over their disabled car:

“When’s the last time you flushed the exhaust?” he asks, and the husband offers “Oh, about a year ago.” “There ain’t no such thing as flushing the exhaust,” he says. “I just wondered what kind of a guy I was dealing with.”

There follows a complex play of interpretations and reinterpretations of meanings and intentions. Mortal threat and playfulness trade places as we, and the husband, and the wife, try to interpret the trucker’s words and gestures. Is he flirting? Preparing an assault? Is there a definitive answer at any point? Again, Flanagan is playing with our prior scripts (prominent among them perhaps the 1997 film Breakdown, though the isolated and vulnerable pair is archetypal enough), alternately fulfilling and frustrating expectations. In the final and most elaborate working-through of the theme, an aimless, recently discarded young man with a growing reputation for his performances in an “air band” – pretending to play instruments, pretending to sing other people’s songs – is rewarded with the sexual perquisites of real rock stars. It’s tawdry, but not. Because it’s not clear that there’s a real self present enough to be degraded. “A part of me was sad that it wasn’t Katie, but another part of me knew that it wasn’t me, either.” A moment comes when he’s asked for his autograph, and he has no idea whose name to write.

The inquiries unfold in landscapes and timescapes that provide little context. The 1984 Olympics play in the background of one yarn. In a story set in 1994, Lorena Bobbitt and Tonya Harding are mentioned. In another, the events of September 11 are the cause of vague unease. North Platte, Missoula, Lincoln, Omaha, these places are famously nowhere, and the action takes place at some remove even from these. “Front and Center” is a purgatorial run along the grid of highways that encounter no obstruction from nature when their abstractions are draped across the plains, two employees of a hopeless little restaurant in pursuit of a promised rendezvous with a meat supplier. Vladimir and Estragon would be at home here, as would Achilles and Captain Ahab – the featureless landscape has always had the one great advantage of forcing one to define oneself without much in the way of props or set.

But again, it is not a sterile intellectual construct. There are hints of coherence; a number of the stories point consistently to a town, Pilgrim Nebraska, where a typical graduating class might have twenty eight people, or Deridan College, somewhere in Colorado, where one works hard for tenure, and then, well, not so much. Little towns that are said, both ruefully and with a twisted sort of pride to be the Meth Capital of the United States. That’s a concrete fact with abstract implications. Similarly, actions have consequences; it is not a world like Don Draper’s where one simply wills a thing never to have happened, and its consequences evaporate. You get somebody fired, they stay fired. Somebody leaves you holding a dog, you’ve got a dog. And just as surely, you’re sure that things will change you – and disappointed when they don’t. The central character of “A Possible Story” realizes a kind of postpartum depression when she finds that becoming Someone Who Has Written A Book did not transform her as she expected it would. Being someone who had a one night stand with a famous writer did…until she realized it made her a cliché…and then much later realized that the intense eroticism of that moment didn’t even get beneath the smooth cloudcover of an ego as big as Jupiter. Famous Writer doesn’t even remember the intimacy that she had long thought of as one of the pivots of the process that brought her into being. She realizes that even if she were to confess this event to her husband, he’d most likely react not with jealousy, but what happened to that girl? In another piece, the husband of a political operative realizes the attractive woman he noticed the candidate squiring around is his own wife, and yet in this frame she seems someone else entirely. When spouses are properly redistributed, he sees what looks like genuine warmth, but after the Emersonian original sin of self-awareness, affection and affectation are inextricable.

This is ordinary, known pain.

The stories keep asking, what happened to that person? Who is this person? Are we the things we say? The things other people see? The adolescent narrator of “The Winning Ticket” is engaged in numerous chronological mirrorings and self-observations, remembering the silent approach of the loss of innocence, retrospectively understanding the gravity of the moment when she wondered why her mother thought of the neighbor-lady as “putting on airs.” “I didn’t understand why it was an air and not Mrs. Silber’s real self, when she seemed, as well as I could tell, to keep the appearance up every day.”

If it’s philosophy, it’s deeply felt. “Summer of Cancer” is the one technically showy piece in the collection, a tour-de-force of persona, impressive really for its understatement. It is a bittersweet allegory of shifting identities which one realizes only after finishing was an allegory. Each of these stories takes it as given that ordinary and even quite undramatic lives involve serious questions. When a postmenopausal woman wonders “who in the world would she be without her children?” it is not a rhetorical question. Every word weighs a pound. What would the world be like in that alternate scenario? Would she have a role at all? One that the self her children brought forth could comprehend?

Ars celare artem est. There are numerous worthy currents in the classic stream of the distinctively American short story. One of them, the best in my view, is the modest rumination, carried out through close observation, in unpretentious prose, of worthwhile people in ordinary circumstances. Flanagan fishes in that stream; she has the eye and intuition to plop her float easily and naturally where things are moving in the depths.

Adam Brooke Davis teaches folklore, medieval studies, writing and linguistics at Truman State University. He has published fiction, poetry, essays and scholarship, and serves as managing editor of GHLL.